Microsoft, a name synonymous with innovation, has a rich history that dates back to 1975. Founded by Bill Gates and Paul Allen, this technology giant started as a small venture in Albuquerque, New Mexico, to create a BASIC interpreter for the Altair 8800, an early personal computer. Over the years, ...

Incident Response, Secret Agent Style

Information Technologies | Caleb Hill | Monday, August 28, 2023![]() In my line of work, casually perusing documents like the SANS 2023 Security Awareness Report is par for the course. Such documents from the SANS Institute, CISA, Kaspersky, Palo Alto, and others use data carefully curated in clean, cool-colored charts to describe futuristic topics like “threat landscapes”, “zero trust”, “cyber security resilience”, and “human risk”. As I scrolled through this particular SANS’ report, it was the last of these topics that wove through each 14-point, sans-serif paragraph: human risk through phishing, human risk in weak passwords, and human risk in incident response.

In my line of work, casually perusing documents like the SANS 2023 Security Awareness Report is par for the course. Such documents from the SANS Institute, CISA, Kaspersky, Palo Alto, and others use data carefully curated in clean, cool-colored charts to describe futuristic topics like “threat landscapes”, “zero trust”, “cyber security resilience”, and “human risk”. As I scrolled through this particular SANS’ report, it was the last of these topics that wove through each 14-point, sans-serif paragraph: human risk through phishing, human risk in weak passwords, and human risk in incident response.

Even the calm, collected SANS researchers had to admit surprise at the inclusion of incident response in the realm of human risk. This was alright; it meant that the companies studied were beginning to understand the importance of configuring technology to respond to cyber threats and configuring the human network to facilitate an energetic, resilient approach to incident response. But how can businesses use their employees best when planning for incident response?

The world of cyber security is constantly optimizing and updating its methods to keep pace with the evolution of information technology, quite often by creating better tools for cyber security professionals. However, what if those cyber security professionals similarly optimized the workforce's abilities whose information and livelihoods they are protecting? This is where the secret agent-style incident response comes in.

Inventing the Incident Response Wheel

Before we get there, however, what is incident response? For a quick refresher, you can look at Intrada’s previous article covering the basics of incident response planning. Both

The number of steps in the cycle varies slightly between the CISA playbook and

- Prepare for potential incidents

- Detect and analyze possible incidents

- Contain, eradicate, and recover from detected incidents

- Review the response process.

The role of an incident response plan in all of this is to coordinate the actions involved in each of these steps to make them flow as seamlessly as possible, reducing time wastage and allowing businesses to recover faster and better than before. Clearly defined decision structures, well-documented emergency numbers, and frictionless incident reporting mechanisms are hallmarks of a good incident response plan.

Spy Network

The structures and mechanisms of incident response are already a well-trodden path, attempting to wrangle the disparate difficulties of human risk into a manageable set of policies and procedures. While documentation is an indispensable piece of properly configured incident response, truly addressing human risk requires more revolutionary methods - like spies.

Let me explain. The intrusion detection systems that fuel cyber incident response activities rely on “agents”, which are software programs installed throughout a local network, to supply them with the information they need to detect attacks. Likewise, with proper training and purposeful inclusion, a business's employees can become nodes on a detection and response network. If provided with the knowledge and resources to report something suspicious and when, where, and how it was, your company’s incident detection system can be equipped with real-life secret agents.

This is where the structure and procedures mentioned earlier are paramount. Secret agents have codewords and secret signals because they have a system. Your incident reporting spies' system must facilitate swift and accurate responses. This way, the cyber incident response team (senior agents) doesn’t have to waste time going over the same ground again to understand better what’s happening.

Including employees in incident response seems nice on paper, but many professionals (sometimes myself included) can be wary of trusting non-technical individuals. Years of help desk experience has taught them always to take customer reports with a grain of salt. Though some admit that making employees into competent, boots-on-the-ground players in cyber security is possible, it still seems too time- and effort-intensive to be worth the shot.

Like most of us, I have experienced mornings laden with little setbacks that leave me running late. On the way to work, my average speed creeps up like a mischievous gremlin had hidden lead in my shoes. However, no matter how fast I go, I only get to work a little earlier than if I had left on time.

The same goes for responding to cyber incidents: the earlier you catch it, the faster it will be resolved. Don’t get me wrong: it matters how good your incident response team is. If you put Inspector Clouseau on the trail of the hound of the Baskervilles instead of Sherlock Holmes, you may get a somewhat subpar result. But even Sherlock Holmes often found himself stymied by cold trails and erroneous information. The less “static” your incident response team must sort through to resolve the problem, the better for your organization (and their sanity).

It HaaSS Potential

This is especially important because advanced persistent threats (APTs) often solely target the human factor in the early stages of their attacks. This leaves no technical traces for the incident response team to analyze and means that human “security sensors” can provide the incident response team with information of a type, scope, and quality that is completely unavailable to technology-level sensors. The human-as-a-security-sensor (HaaSS) approach was first coined in 2017 by a paper that proposed and tested a HaaSS system monikered Cogni-Sense that utilized live reporting from users compared to technical detection controls to identify a variety of social engineering threats.

These threats (such as a malicious PDF file sent over Google Drive and a Facebook phishing message) were largely unnoticed by technical controls on the platforms themselves (Google, Facebook) because they did not break the platform's rules. They aimed to deceive users rather than exploit vulnerabilities. The HaaSS prototype, on the other hand, allowed users to report these social engineering attempts and thereby caught most of these attacks, performing significantly better than built-in security safeguards.

These experiments show that developing a network of individuals within a company that can provide information about attacks and threats targeting the company has incredible potential to augment security. Such a network could offer more timely detection for attacks and give security analysis and incident response teams information about a section of attack anatomy rarely seen using more traditional security tools. User error is the blind spot of cyber security (and IT support). Suppose we improve users’ ability and confidence in reporting threat information and implement a system within which they can use these skills. In that case, we can go a long way towards expanding cyber security’s field of vision. This, in turn, dramatically augments the efficiency and efficacy of the response efforts of a company’s IR team.

Empowerment with a side of inaccuracy

This may seem like an optimistic claptrap to seasoned denizens of the business world. How could security’s weakest link (the human element) go from zero to hero with a snap of the fingers? There must be a catch.

To some extent, there is. Incident response teams have preferred technical controls for years to gather the information they use to detect incidents because of the output's discrete, binary nature. Like it or not, computers will only ever do what they are told, so inaccuracy in data is due to a lack of data literacy, incorrect configuration, or insufficiently sophisticated technology. This gives objectivity to evidence gathered from security information and event management systems (SIEMs) or intrusion detection systems that appeal to security professionals.

With that in mind, the catch becomes clear: any information gathered from hypothetical HaaSSs will be subject to the familiar pitfalls of human error and bias. We may collect advantageous data from human security sensors, but how can we trust that data?

One of the teams that began further developing the HaaSS idea explored using targeted questionnaires to follow up with users to improve the quality of the information reported. Either way, the cyber security incident response data that can be “mined”, so to speak, from the minds of humans is fundamentally different than what can be accessed via technical controls such as Windows Event Log. These attributes make it more challenging to process traditionally, initially making them more intimidating. However, with a pinch of paradigm shift and a healthy dollop of innovation, human-sourced data can become a delightful dish of incident response improvement.

Casing the Joint

Sometimes, cyber incidents still bear a strong resemblance to old-fashioned heists. One such hack (with the suitably opaque name “DarkVishnya”), was carried out by cybercriminals who bluffed their way onto business premises to plug devices into the local network (source) discretely. These attacks successfully targeted multiple banks, lending themselves even further to the heist vibe.

The kicker for the “secret agent style security” model is that steps one and two of these attacks could have been detected and reported by well-trained security secret agents. Though an

When the employees of an organization perform incident response secret agent style, they have an opportunity to sniff out cyber security threats and attack vectors that would have otherwise gone unnoticed. This saves your company from cyber attacks that would have run rampant throughout your data and systems without a transparent reporting infrastructure and a well-educated employee population.

Are we there yet?

Though it may appear that we’ve jumped deep down a rabbit hole, bouncing from government guidelines to HaaSS systems to bank heists, we pop up in familiar territory: incident response. The predicate to all of this exploration was how companies can improve incident response for cyber security incidents. Having an incident response plan and a chain of reporting is essential, and it’s a place to start; however, it’s not a place to stop. The nascent development of HaaSS systems proves that the sky is the limit for human usefulness in augmenting incident detection and, thereby, incident response. We can cultivate a strong incident reporting culture by making incident response plans straightforward while systematically increasing information technology literacy across the company.

Though HaaSS systems have yet to hit the market, the principles behind these systems have the potential to revolutionize the incident response paradigm for the better. Imagine incident response teams whose incidents are made up of not only a collection of event log entries and suspicious user logins but also a verified and correlated set of reports from users themselves. In the cat-and-mouse game of incident response, including human input can give incident responders the insights they need to recognize and remediate unwanted intrusions effectively.

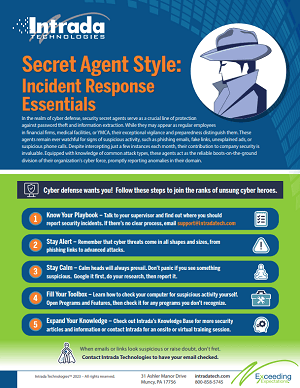

Cybersecurity Awareness Poster

Leveraging SEO for Business Growth

In an era where digital presence determines the success of a business, Search Engine Optimization (SEO) has emerged as a vital tool to stay competitive in the market. SEO is a strategic process that enhances your website's visibility in organic search results, effectively driving more traffic. But h...

Contact Us

- 800-858-5745

31 Ashler Manor Drive

Muncy, PA 17756

Office Hours

Monday - Friday

8 AM - 5 PM EST

Intrada Technologies

Copyright © 2025 - Intrada Technologies - Privacy Policy and Disclaimer

Our website uses cookies and analytics to enhance our clients browsing experience. Learn More /